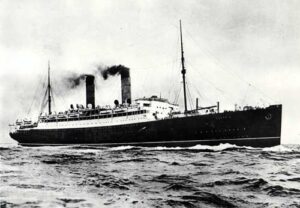

The story of one of the most tragic ships to come out of a Tyneside shipyard.

The R.M.S. Laconia, owned by Cunard White Star, was built by Swan Hunter and Wigham Richardson just a few years after the end of the First World War. She replaced a war loss of the same name and was launched from the Tyne yard in the spring of 1921. She made her maiden voyage the following year from Southampton to New York and became famous for being the first Cunard liner to make a world cruise. She made her first world cruise from New York in January 1923, lasting over four months and calling at 22 ports.

She was requisitioned by the Admiralty as an armed merchant cruiser at the beginning of the Second World War, and was subsequently employed on convoy escort duty.

In the summer of 1941 she refitted as a troop transport serving in the middle east; on September 12 th 1942 she was in passage from the middle east to the UK carrying some 80 civilians, 268 British Army soldiers, about 1,800 Italian prisoners of war, and 160 Polish soldiers (on guard), and was struck by a torpedo from Kriegsmarine submarine U-156 under the command of Kapitänleutnant Werner Hartenstein off the coast of west Africa, 130 miles north east of Ascension Island. A number of Italian POWs were killed instantly. After a second torpedo struck, the ship – which was carrying women and children – she was ordered to be abandoned and quickly sank.

What happened next has always been a subject of controversy. Realising that the casualties included civilians and Axis prisoners, Kapitänleutnant Hartenstein made a rescue, and having waited nearly three days on the surface for help, U-156, with three other German submarines, Red Cross flags draped across their decks, headed for the African coastline, with lifeboats in tow and hundreds of survivors standing on their decks.

Photo by Kapitänleutnant Hartenstein

At 12:32 on 16th. September, they were attacked by a US bomber aircraft (B-24 Liberator) with bombs and depth charges. One of these was a direct hit on a lifeboat while others straddled the submarine itself. Naturally, giving priority to the safety of his crew, Hartenstein ordered the survivors on his deck into the lifeboats, and cast the lifeboats adrift. The submarines dived and escaped.

About 1600 Laconia passengers perished, and in all, some 1,100 passengers survived (Figures vary), mostly picked up by Vichy-French ship Gloire. The last four survivors were not picked up until 21 October and were the only ones left alive in a lifeboat that had originally contained 51 people.

This incident led German Admiral Dönitz to issue the Triton Null Order which came to be known as the “Laconia Order”, expressly forbidding submarine commanders from rescuing survivors from torpedoed ships. The US Navy issued a similar order in the Pacific.

At Nuernberg after the war, Dönitz stood trial for war crimes and the Laconia Order was used as a basis of indictment against him. Most surprisingly, he received support from some of the most respected figures in the US Navy, including Admital Chester Nimitz who came to his defense and said that the United States had operated under the same engagements of unrestricted warfare.

Despite the evidence of allied practice, Dönitz was convicted of war crimes by the Nuernberg Tribunal and sentenced to 11 and a half years in Spandau prison.

The U-boat crews deeply resented this action and felt that they were being prosecuted for the threat they had posed to the allies rather than for war crimes.

During her next patrol, on 8th March, 1943, Hartenstein and the entire crew of U-156 were

killed in action by depth charges from a US Catalina Flying Boat aircraft, east of Barbados.

Survivors

Gladys Foster wrote a detailed description of the sinking, the rescue and her subsequent two month internment in Africa. Gladys was the wife of Chaplain to the Forces, Rev. Denis Beauchamp Lisle Foster who was stationed in Malta. She was onboard the ship with her 17-year-old daughter, Elizabeth Barbara Foster, travelling back to Britain. During the mayhem of the sinking the two were separated and it wasn’t until days later that Gladys discovered her daughter had survived and was on another raft. She was urged to write her recollections not long after landing back in London.

Elizabeth married Major Peter Charles Crichton Gobourn in 1953. She died in Cheltenham in January 2010 aged 82 (sic) and was survived by her three children and seven grandchildren.

Frank Holding (Merchant seaman) also survived the sinking and is still alive and looking forward to his 90th birthday in 2011

Doris Hawkins (missionary nurse, SRN, SCM) survived the Laconia Incident and spent 27 days adrift in Lifeboat no.9, finally coming ashore on the coast of Liberia. She was returning to England after five years in Palestine, with a fourteen month old girl named Sally who unfortunately was lost to the sea as they were transferred to the lifeboat. Doris Hawkins wrote a pamphlet entitled “Atlantic Torpedo” after her eventual return to England, published by Victor Gollancz in 1943. In it she writes of the moments when Sally was lost “We found ourselves on top of the arms and legs of a panic-stricken mass of humanity. The lifeboat, filled to capacity with men, women and children, was leaking badly and rapidly filling with water; at the same time it was crashing against the ship’s side. Just as Sally was passed over to me, the boat filled completely and capsized, flinging us all into the water.

I lost her. I did not hear her cry even then, and I am sure that God took her immediately to Himself without suffering. I never saw her again”.

Doris Hawkins was one of 16 survivors out of 69 in the lifeboat when it was cast adrift from the U-boat.

She spent the remaining war years personally visiting the families of people who perished in the lifeboat, returning mementoes entrusted to her by them in their dying moments. In Doris’s words “It is impossible to imagine why I should have been chosen to survive when so many did not. I have been reluctant to write the story of our experiences, but in answer to many requests I have done so; and if it strengthens someone’s faith, if it is an inspiration to any, if it brings home to others, hitherto untouched, all that “those who go down to the sea in ships” face for our sakes, hour by hour, day by day, year in and year out – it will not have been written in vain”.

22 Feb 2010 – TRAGIC WALLSEND SHIP IN BBC DRAMA.

The last desperate hours of the transport ship Laconia, before she sank with the loss of hundreds of lives, has been dramatised for the BBC by acclaimed writer, Alan Bleasdale, of Boys from the Blackstuff and GBH fame.

Another War, another Laconia.

On 27th July 1911, the original RMS Laconia was launched, also at the Wallsend yard; she had taken the place on the stocks of her sister ship Franconia. The launching ceremony assumed quite an international character in that it was performed by Mrs. Whitelaw Reid, wife of the American Ambassador in London, while the word Laconia, in addition to its Grecian associations, is an old name for part of New Hampshire, U.S.A., in which State is also situated the town of Laconia.

She, like so many other liners when war broke out in 1914, had her civilian career abruptly terminated and was pressed into service as an armed merchant ship; she performed sterling work in her role in the Indian Ocean and the South Atlantic for two years, returning to Cunard in 1916, when she took up her station in the Atlantic, leaving from Liverpool on the 9th September bound for New York.

On 17th February 1917 she departed New York, bound for Liverpool on what was to be her last voyage, being sunk by German submarine U-50; on board was a crew of 216 and 73 passengers, including an American journalist – a 29 year old handsome adventurer, Floyd Phillips Gibbons who as foreign correspondent with the Chicago Tribune had already achieved legendary status for his daring and bravery in reporting on the Mexican border war.

He writes it all down thirty hours after the event, with details of the dead, giving a highly descriptive account of the efforts to get into boats, the confusion, the eventual haunting loss of the liner as she rears into the night sky and slips down, lost forever, and of the sickeningly eerie approach of the glistening killer that had sent her to her grave.

Only twelve perished, but of that relatively small loss were three Americans, two of them mother and daughter from Chicago . The story would be printed in the Chicago Tribune and it took America by storm.

And it was this story, the loss of the Tyne-built Laconia on the 25th February 1917, Floyd Gibbons would maintain, was the final straw for President Wilson, the man who was re-elected by a narrow victory in 1916 with the slogan, “He Kept Us Out of War,”

Five weeks after it was printed in the Tribune, America abandoned neutrality and entered the Great War.

Gibbons’ account can be read here:

http://www.gjenvick.com/CunardLine/Articles/1918-TheSinkingOfTheCunardLaconia.html

in excerpts from his book,

“And They Thought We Wouldn’t Fight”

N.B. It is often thought that the sinking of the Lusitania brought the U.S.A. into the war; in fact our Mauretania’s sister ship R.M.S. Lusitania was sunk off the coast of Ireland on 7th. May 1915.

In November 2008, the wreck of the Laconia was discovered 160 miles off Fastnet by Odyssey Marine Exploration/Treasure Hunters. The company is still in dispute with H.M. Government over rights to the ship and her £3 Million in silver bullion (50 Million by one source).